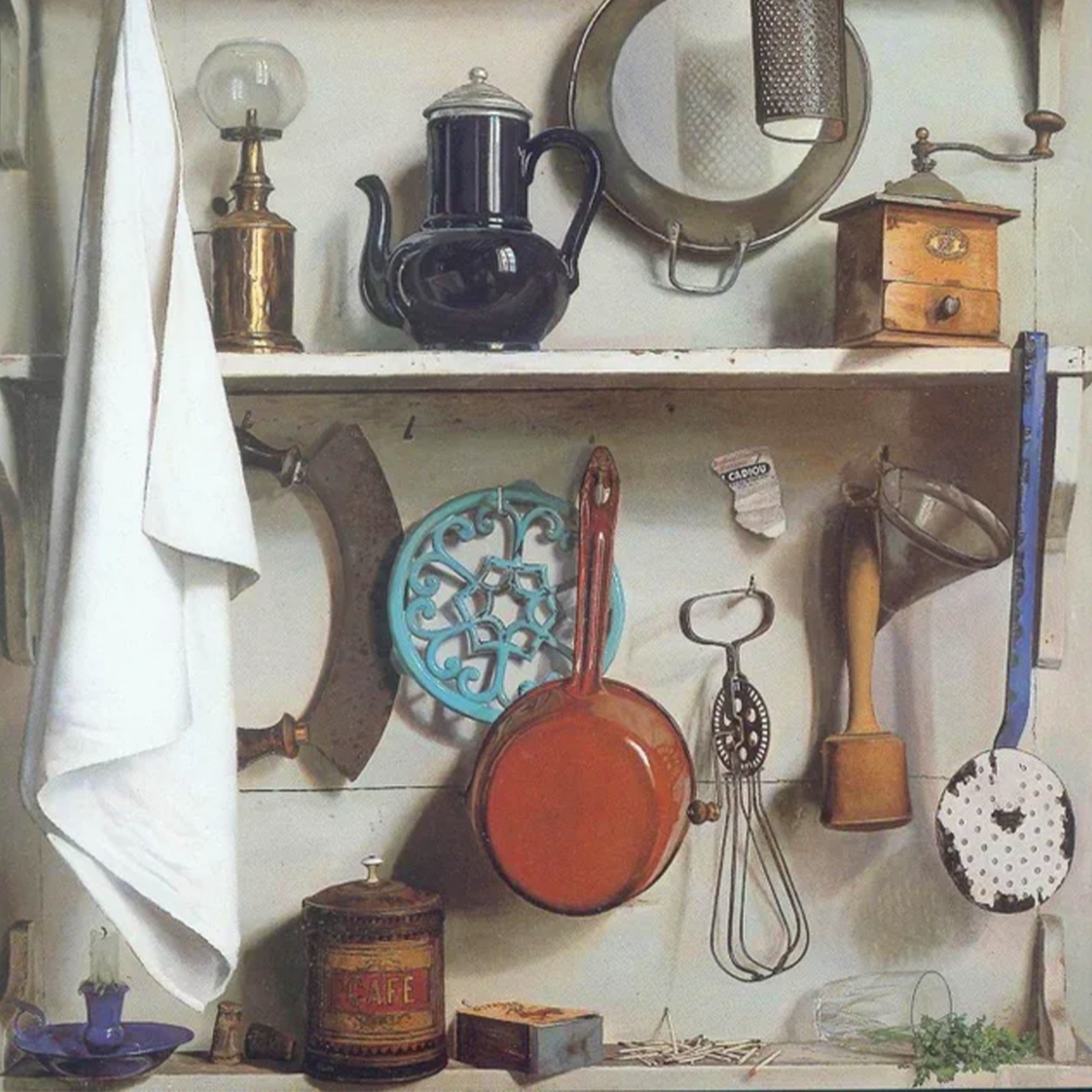

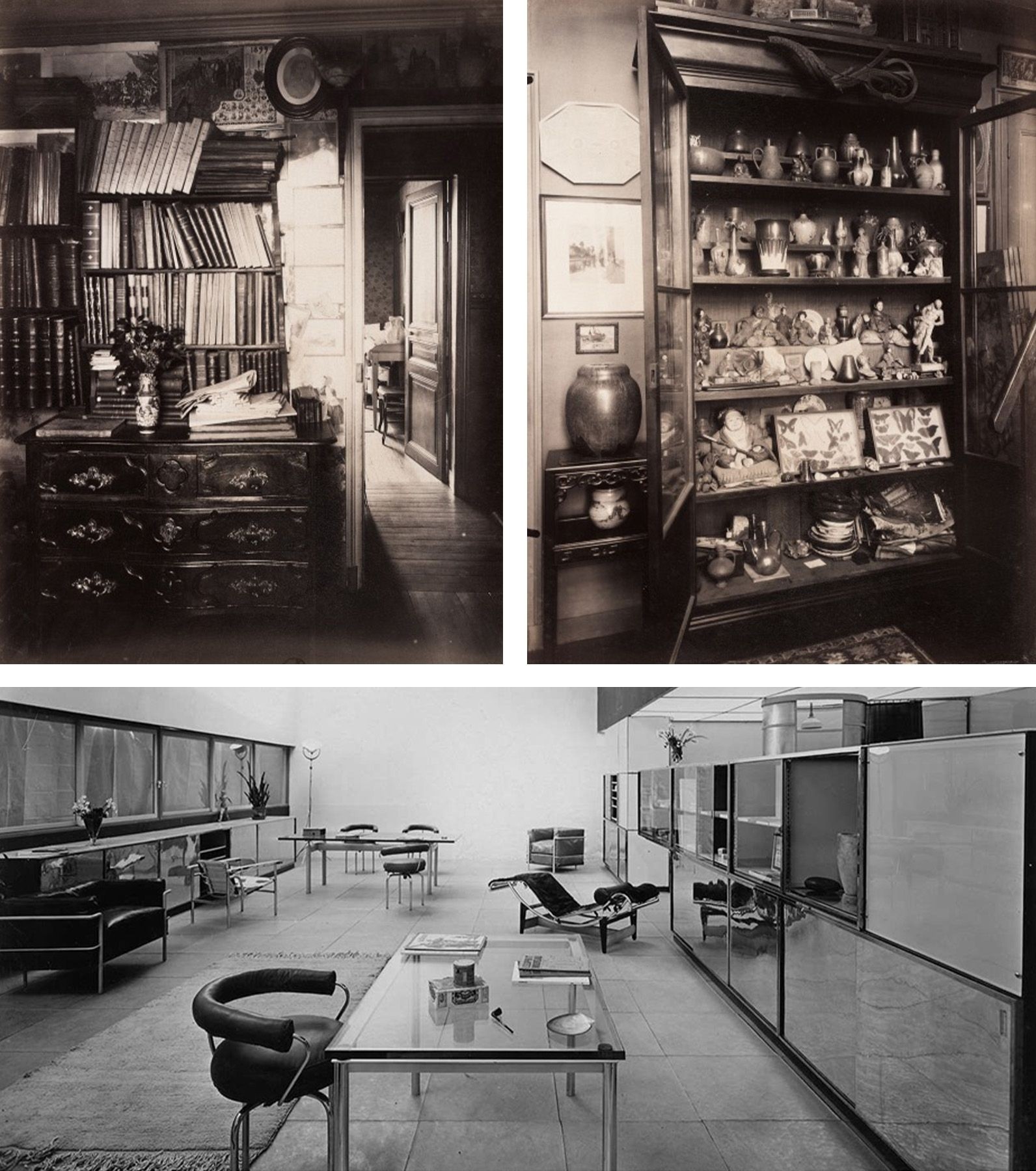

Storage covers a highly material dimension related to functional qualities—that of being able to dispose of our possessions in our home while maintaining a peaceful living space with intact spatial qualities. But this theme also touches upon more personal and less tangible dimensions that are often embodied outside the dwelling itself, traditionally through places such as garages, cellars, or attics—indulging in home improvement and undertaking to repair objects thanks to a few stored tools and materials, preserving memories in their material thickness, or passing on photos or family heirlooms. The ability to store also takes on a certain flexibility, by allowing for the storage of furniture while moving out or taking a trip aboard, or following a separation, or for putting one’s belongings away when renting out one’s home. It is a source of adaptability to different lifestyles. Storage can meet one-off or fluctuating needs over the course of one’s lifetime. For instance, young parents might store away boxes of clothes from their first child for a few years until they can be handed down to a second child.

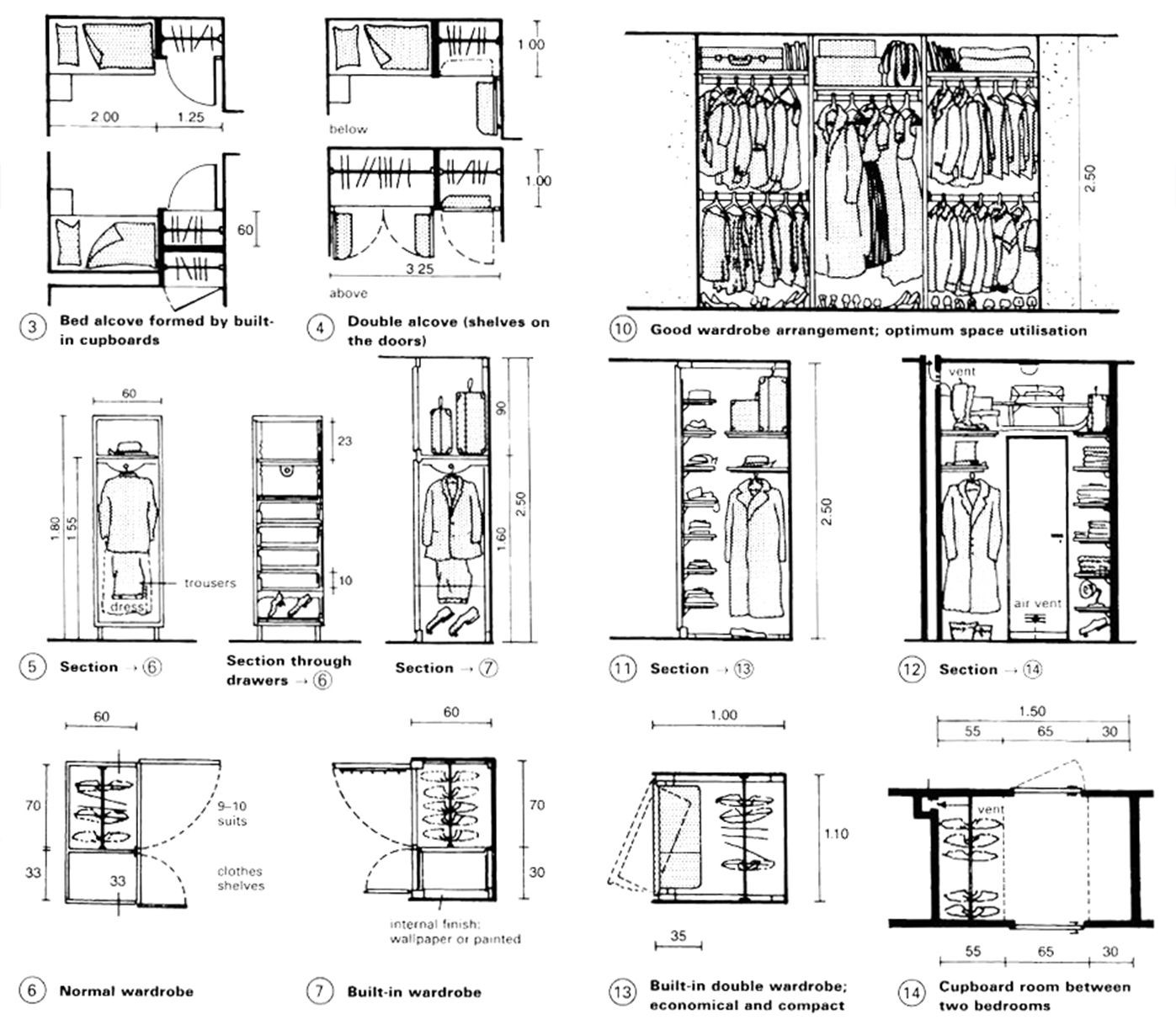

However, under the current conditions and constraints of the construction of collective housing, these qualities cannot always be offered within the housing unit itself. Faced with decreasing surfaces, it is obviously essential to advocate for making them more generous, but also for creating cellars or utility rooms on the landing—private extensions, just like garages and attics are for detached houses.

The sharing of spaces, on the scale of the building or the neighborhood, is another possibility that should be explored. We need to try to address our occasional needs for storage.

Most large cities are now experiencing a decrease in the use of private cars. Many storage spaces are being freed up from the vehicles they were originally intended for. The thousands of square meters once meant for cars can partly be put to use for “democratizing” the access to storage in urban contexts. The repurposing of a former parking lot on Rue du Grenier-Saint-Lazare in the 3

d arrondissement of Paris that is being pursued by Sogaris is one such example. It will accommodate storage spaces for neighborhood shops, but will also offer spaces for local residents, who will be able to temporarily reserve small spaces to store a few items there.

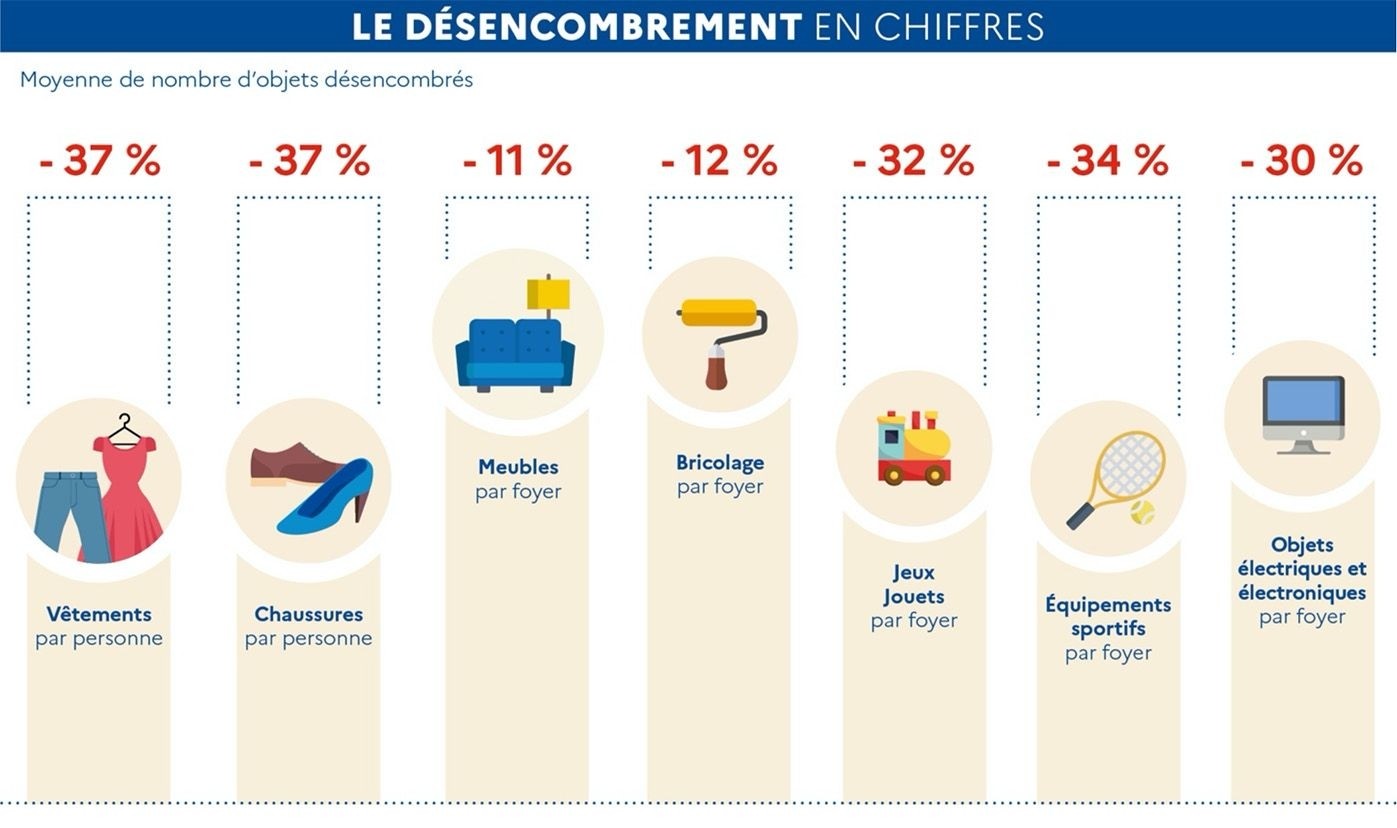

The “commons” might also be heavily leveraged to improve the circular economy. Consider, for example, that power drills are used on average for only a short ten minutes over their entire service life.

[17] Faced with this reality, it seems relevant to offer, on the scale of a building or a neighborhood, the pooling of certain objects that are used only infrequently, such as DIY tools or a fondue set, as an alternative to purchase. The “commons” can be leveraged to foster awareness and facilitate giving, sharing, or second-hand purchases, under the form of a community-based resource recovery center or a “library of things” for example. They form a partial answer to the problems of excessive consumption mentioned earlier, as they can become a stepping stone towards an alternative form of consumption based on repair and second-hand use. This cannot be achieved without a dedicated storage capacity, however.

Ranging from shared facilities on the ground floor of buildings to community-based resource recovery centers and self-storage services, several models are emerging. In the first of these models, the residential real estate industry takes on the responsibility of meeting the storage needs of residents. In the second model, the responsibility of developing “libraries of things” is explored based on the model of the municipal library by the local government. If neither of these models comes into being or if they prove to be insufficient, then paid services will take over and address that need. And the self-storage sector is, in fact, booming. But doesn’t an organized dependence on a paid service imply a

de facto discrimination in access?