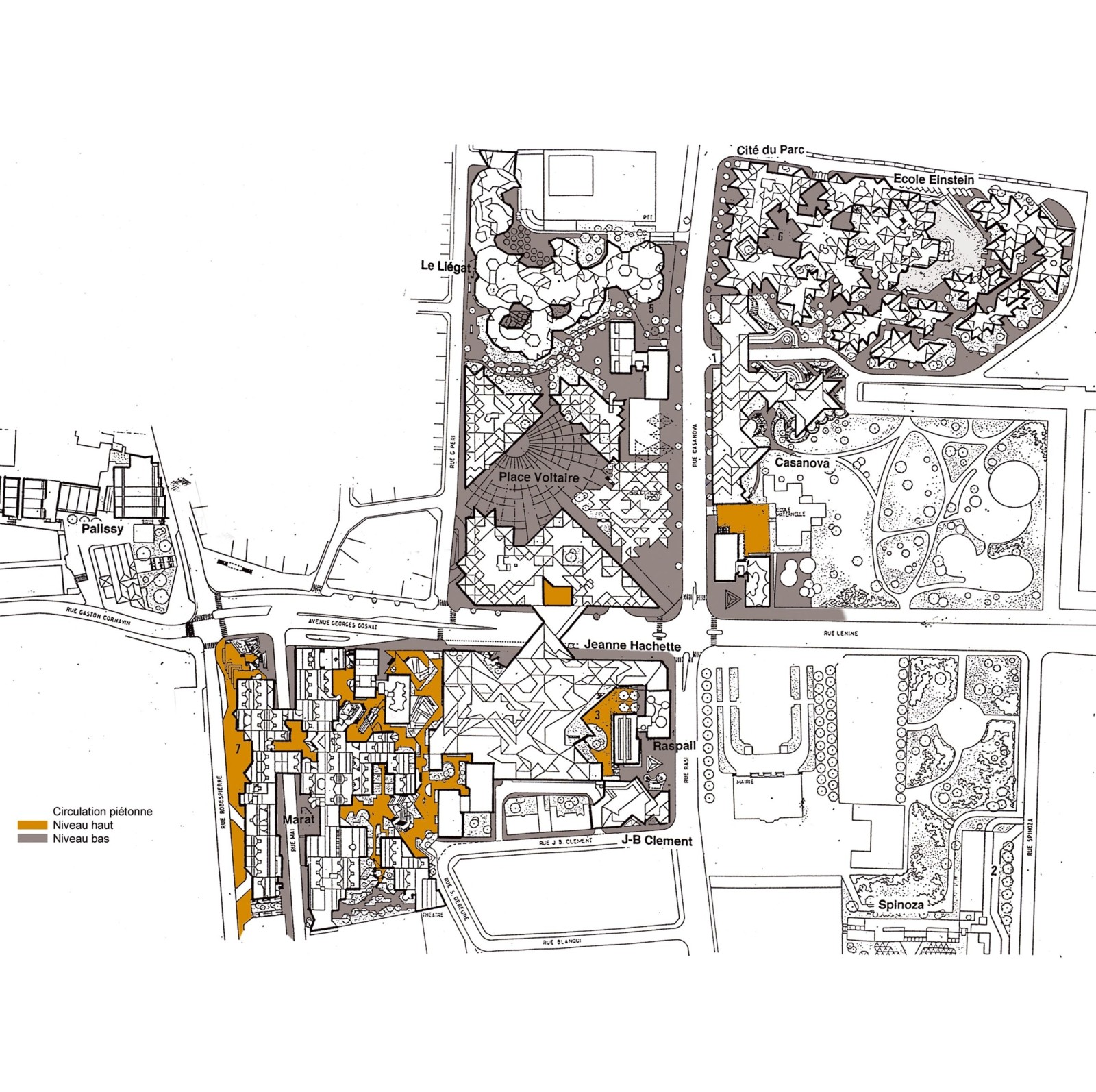

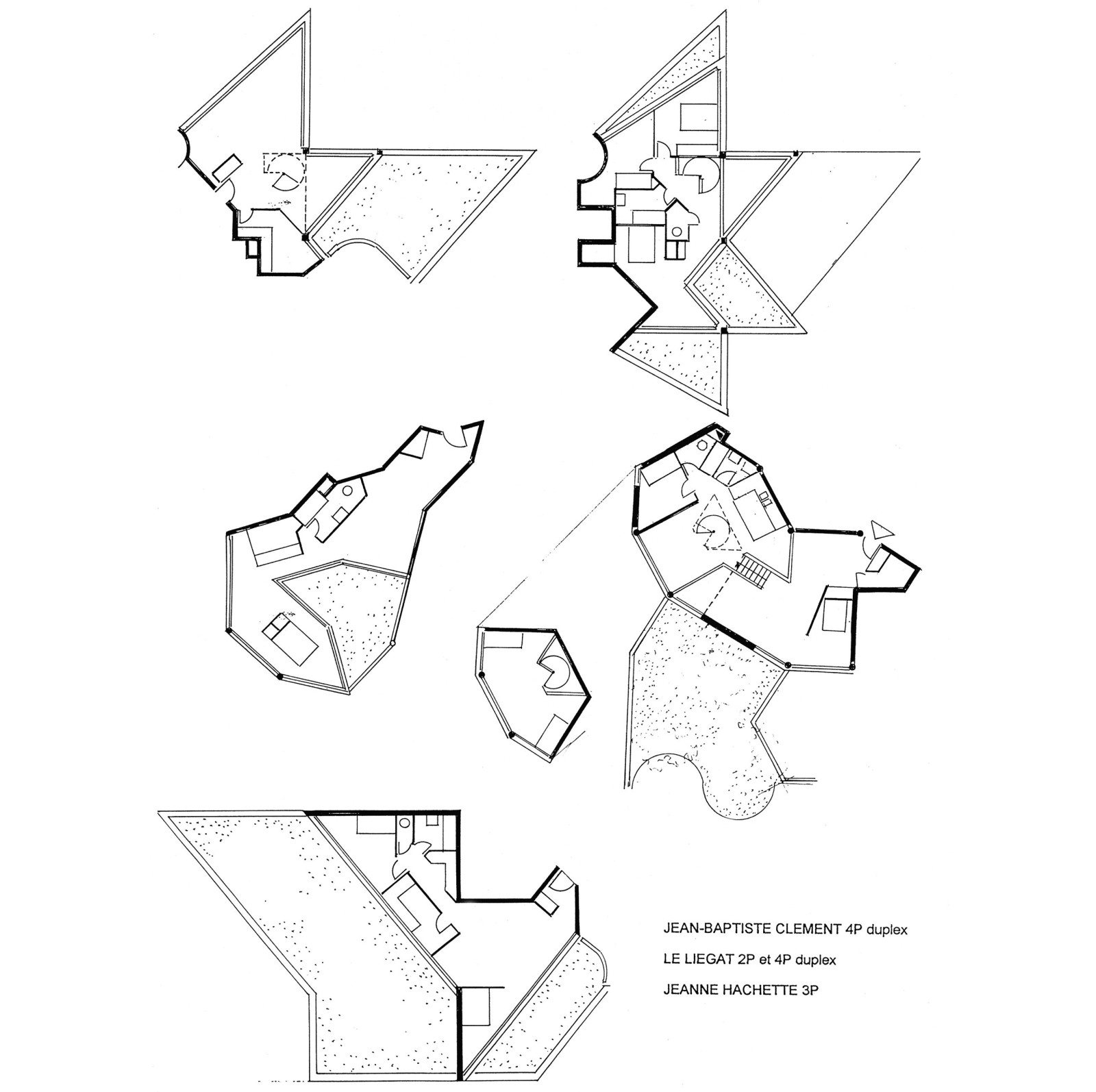

The public works programme that the communist-run town of Ivry-sur-Seine launched in 1962 for its renovation lasted for more than twenty-five years. It was only at the end that the main thrust emerged clearly and that the project took shape; in the meantime people grew accustomed to living in provisional surroundings, with changes taking place in bits and pieces, and bursts of demolition depending on the state of the municipal cash-flow, and buildings going up like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle as yet illegible. The first operation was the appearance in 1968 of a tower block of ninety-six apartments opposite the venerable town hall, causing some perplexity in the municipality. The next stage was in 1970, when Jean Renaudie showed the future inhabitants the model of the Casanova building and its eighty apartments: a founding moment. There was some intrusion of political developments into daily life, and doubts as to the legitimacy of the project (was it really suitable for the working class ?), the desire to complete what had been started, or to be done with the whole thing, and the ever-pressing need for new housing. Here we merely describe one aspect of the story: what those who worked on the transformation of the district wanted to achieve, the builders, the architects, but also those who commissioned the work, and whose passionate involvement made the operation possible.

The public works programme that the communist-run town of Ivry-sur-Seine launched in 1962 for its renovation lasted for more than twenty-five years. It was only at the end that the main thrust emerged clearly and that the project took shape; in the meantime people grew accustomed to living in provisional surroundings, with changes taking place in bits and pieces, and bursts of demolition depending on the state of the municipal cash-flow, and buildings going up like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle as yet illegible. The first operation was the appearance in 1968 of a tower block of ninety-six apartments opposite the venerable town hall, causing some perplexity in the municipality. The next stage was in 1970, when Jean Renaudie showed the future inhabitants the model of the Casanova building and its eighty apartments: a founding moment. There was some intrusion of political developments into daily life, and doubts as to the legitimacy of the project (was it really suitable for the working class ?), the desire to complete what had been started, or to be done with the whole thing, and the ever-pressing need for new housing. Here we merely describe one aspect of the story: what those who worked on the transformation of the district wanted to achieve, the builders, the architects, but also those who commissioned the work, and whose passionate involvement made the operation possible.