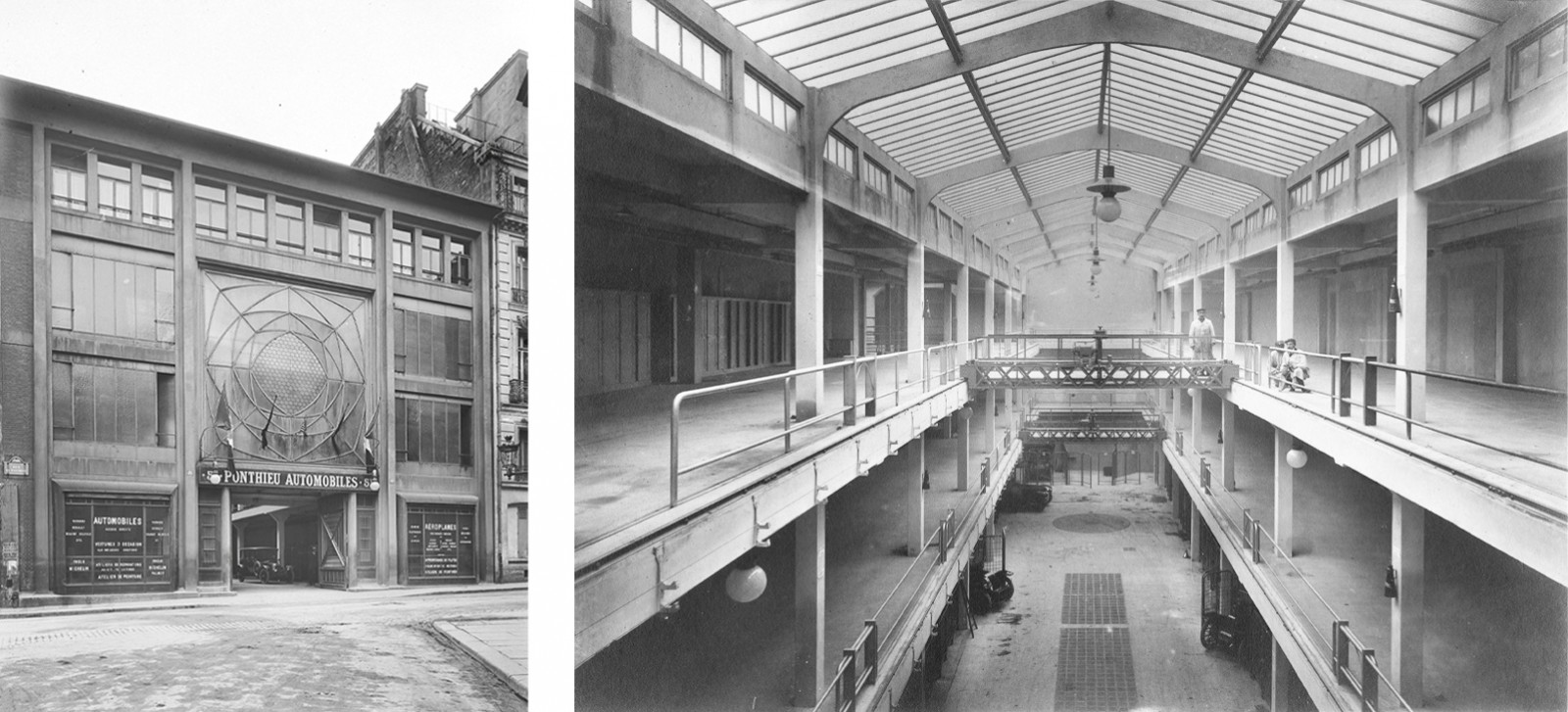

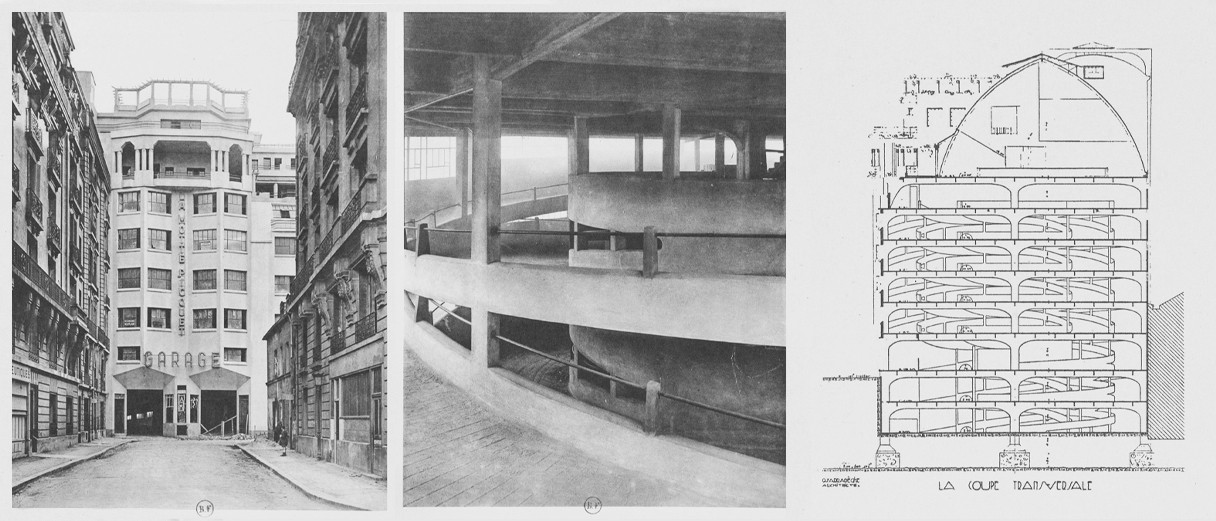

At the end of the 19th century, the Paris region was the cradle of the automobile revolution. The rapid and spectacular rise of the "automobile" was accompanied by the appearance of new building archetypes, specifically designed for this new technical object. This historical account presents the highlights of the construction of these buildings alongside those of the automotive revolution and Parisian mobility.

It starts with the arrival of the automobile in the French capital during the Belle Époque, moves on to the prolific interwar years, then to the so-called thirty “glorious” years of the postwar economic boom, the Trente Glorieuses (perhaps now to be best remembered as the “Thirty Polluters?”), and finally enters the time of disenchantment and the gradual end of the car age after the oil shocks of the 1970s, when new uses remain to be invented for obsolescent buildings.

Each of these major stages is illustrated by several buildings, selected for their outstanding architectural, urban or structural value, or because they are particularly representative of the period. This is of course a subjective selection from a corpus that is far from being exhaustive, to be found in the booklet published in conjunction with this chronology. The panorama or architectures and landscapes generated for and around the automobile remains an open field of research, one that focuses on buildings that are still poorly understood and recognized.