In his latest book, Anselm Jappe unfurls a critical history of concrete as a material, starting with its genesis and moving on to its global expansion and then its supremacy. He questions the intentions of its numerous zealots, ranging from the working-class proletariat to international capitalist class, and discusses the effects of this material that exhaust the land and destroys the environments it colonizes. Can we then cure our addiction to concrete? How so? The article focuses on these two questions, using an inquiry into the common construction material in order to question the way we build our cities.

My book Béton – Arme de construction massive du capitalisme [Concrete. Capitalism’s Weapon of Mass Construction] (L’Échappée, 2020) gained a level of traction that ultimately took even myself by surprise. Naturally, ever since I was young, I’ve always heard complaints about “gloomy concrete housing estates”, about concrete, always associated with “grayness.” But compared with nuclear power and oil, with plastics and pesticides, concrete maintained an air of seeming “innocence”. We used to say that it was poorly used rather than blameworthy in its intimate nature. Little by little, even the most ardent “progressives”, had to admit that there could be no “communist” use of nuclear power, nor could there be any pesticide-driven “green revolution” in poor countries without killing the rest of living along with the parasites. Concrete, on the other hand, long continued to be perceived as a material that primarily warranted moderate and appropriate use (as well as being coated in colors). To have concrete—as a material—bear the whole responsibility of the “inhospitableness of our cities” (Alexander Mitscherlich), and particularly of our suburbs, would have seemed just as illogical as to try to explain war through the existence of iron.

Many grievances against concrete have accrued over the past decades however, and they now seem to be ready to be expressed in broad daylight. Some of them are based on scientific evidence and are beyond dispute: concrete isn’t “neutral” with respect to health and the environment. Its production uses a large amount of energy and emits huge volumes of CO2. Lime quarrying damages mountains. The need for huge masses of sand leads to the devastation of rivers, beaches and lakes throughout the world, with many adverse consequences on the environment and the lives of the local inhabitants. Cement dust can cause respiratory ailments, and concrete floors can cause postural issues. Concrete waste is theoretically recyclable but nevertheless frequently dumped somewhere due to cost. In cities, concrete results in heat islands that, combined with air pollution, adversely impact public health, and impose the use of another source of pollution: air conditioning. Soil artificialization, which is everywhere proceeding at a remarkable pace, smothers the land and causes severe, and sometimes dramatic, land cover change when heavy rain occurs.

These are “technical” drawbacks for which other technological solutions, paradoxically enough, are often put forward for remediation purposes, or strengthened regulatory constraints. Slightly higher taxes on coal, a sprinkling of state subsidies to make recyclable more convenient… Is that what this is all about?

In my book, I point to another level of the issue that is probably more controversial. When reinforced with steel, concrete has a life expectancy of approximately fifty years—beyond that, it requires expensive maintenance on a continuous basis, which can also fall short, as was the case with the collapse of Morandi Bridge in Genoa. Nevertheless, this short lifespan can still be seen as an advantage, just as with other forms of planned obsolescence: buildings can be continuously replaced, thereby fuelling the economy, which creates jobs, income, and growth—and saves us from the tedium of having to live with buildings from fifty years ago, as outdated as last year’s smartphone. Endless “creative destruction” is the soul of capitalism, as we’ve known since Joseph Schumpeter. It isn’t however always very good for the environment, nor for public finance—but, insofar as it makes it possible to save the fetish of growth year after year, this form of economic religion continues to have its theologians and its devotees.

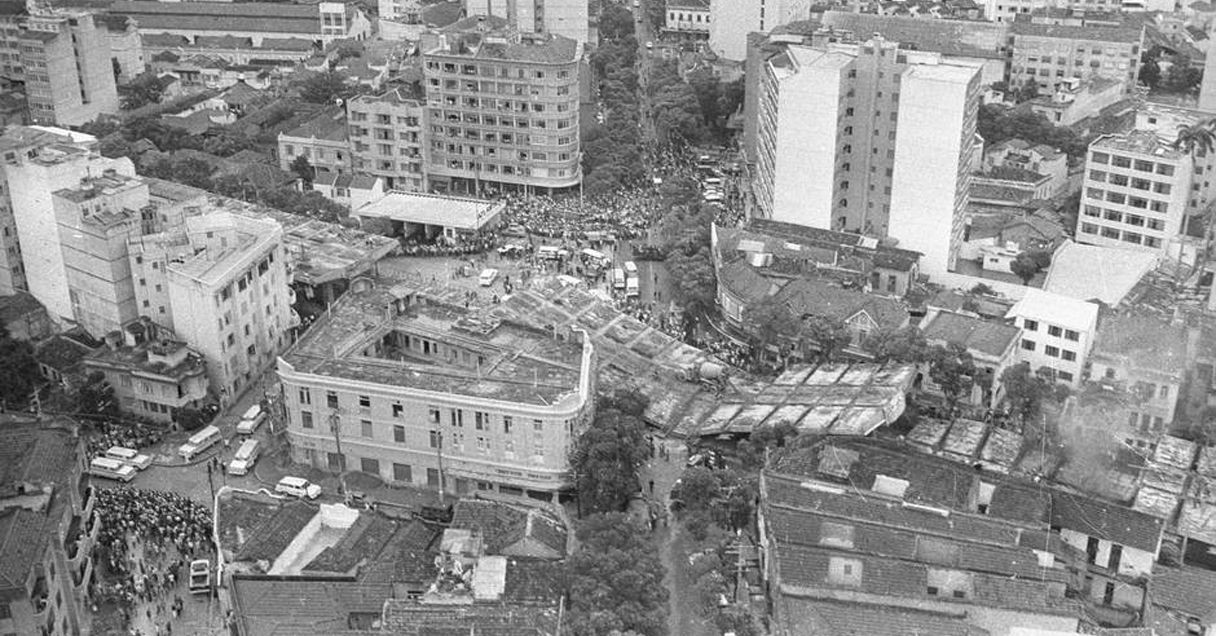

There is a wider context to this discourse however. Another criticism that can be levelled at concrete is, according to others, on the contrary, its greatest merit: having made twentieth-century architecture possible. The largest dams, bridges, highways, nuclear plants, and skyscrapers wouldn’t exist without concrete, nor would the shantytowns found all over the world, the “masterpieces” of celebrity architects, suburban tract housing, or high-rise housing estates. The right and the left, communists, fascists and democrats have resorted to concrete. It lies at the very heart of one of the core businesses of global capitalism—construction—and was often celebrated by anticapitalist forces in their capacity as a “people’s” or “proletarian” material.